The AI infrastructure race: India steps in, gap remains

There is a number that sits at the center of every serious conversation about India's AI ambitions, and it is not the kind of number that gets repeated at press conferences. The US is projected to spend more than $0.5 trillion on data center infrastructure in a single year. India's entire publicly accessible compute pool, every GPU available to every enterprise and researcher in the country right now, is 38,000. Not 38,000 data centers. Not 38,000 racks. Thirty-eight thousand individual processors, priced at ₹65 per hour under a government mission designed to make AI compute affordable.

That number is the context in which everything that happened at the India AI Impact Summit needs to be read. The Summit produced a week's worth of announcements, GPU additions, a domestic foundation model, a chip supply-chain coalition, a governance framework, and each one was real in its own way. But announcements and deployed infrastructure are different things, and the distance between them is exactly where enterprise leaders make expensive mistakes. What follows is a layer-by-layer account of what India's AI infrastructure stack looks like today, how it compares to the US, China, and Vietnam, and what C-suite teams should actually do with the information before their next procurement cycle.

Compute: The Numbers Tell the Story

India's AI Mission operates its 38,000-GPU pool at ₹65 per hour, a government-set rate designed to make sovereign compute accessible without routing workloads through hyperscaler pricing. MeitY minister Ashwini Vaishnaw announced India will add 20,000 more GPUs "in the coming weeks," bringing the public pool to 58,000. The announcement named no chip vendor, no deployment location, and did not confirm whether the ₹65/hour rate carries over. Until those details are public, 38,000 is the only number procurement teams should plan around.

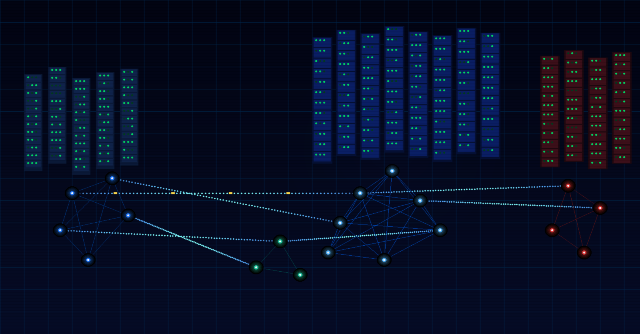

The US has no national compute program, its GPU capacity lives inside hyperscaler infrastructure built by Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta, funded by capital expenditure that drove the $0.5 trillion projection. China is building a National Integrated Computing Network under its "Eastern Data, Western Computing" initiative, routing workloads from demand-heavy eastern cities toward energy-surplus western provinces. RAND Corporation describes this as an industrial policy, not a market response. Vietnam is new to the race, building across three data center locations through a G42 and Vietnamese consortium agreement, with no GPU count confirmed publicly.

India's 58,000-GPU target, once realized, is a meaningful sovereign resource. For regulated industries like banking, healthcare, and defense-adjacent, the ability to run workloads on India-resident compute at a fixed rupee price matters independently of how the number compares to what Beijing or Silicon Valley can deploy.

Sovereign Models: The One Thing That Is Actually Done

The clearest deliverable from the Summit is BharatGen. The suite includes Param-2, a text foundation model with 17 billion parameters covering 22 scheduled Indian languages, alongside speech-to-text, text-to-speech, and two document-processing models, DocBodh and Patram.

The 17 billion parameter count places Param-2 in the mid-range of publicly available models globally. Meta's Llama 3 runs from 8 billion to 70 billion parameters. Chinese labs have released models across similar ranges. What the BharatGen launch changes is not a performance benchmark, those take time to accumulate independently, but the sourcing option set. Before this launch, an Indian enterprise building a Hindi, Tamil, or Bengali NLP application had no domestically built alternative to multilingual models trained abroad, with no visibility into data provenance or language depth. That constraint no longer applies uniformly.

Governance: A Framework Is Not a Regulator

The India AI Governance Guidelines propose three new institutions: an AI Governance Group, a Technology and Policy Expert Committee, and an AI Safety Institute, organized around seven principles called "sutras." None of the three has statutory authority or an operational enforcement mechanism. Compliance teams designing AI deployment architectures around these bodies are building for legislation that has not passed.

The contrast with peer jurisdictions is instructive. China's Cyberspace Administration has generative AI regulations already in effect with penalties attached. The US picture is fragmented across executive orders, NIST frameworks, and FTC guidance, but parts of it carry enforcement teeth. India is at the framework stage. The direction is clear, but the timeline and mechanism are not. Enterprise legal teams should design to what is enforceable today, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, IT Act obligations, and sectoral rules from RBI, SEBI, and IRDAI, and treat the proposed institutions as a forward signal rather than a current compliance environment.

Supply Chain: A Coalition With Unpublished Terms

India joined Pax Silica, a coalition described as securing the silicon stack from raw minerals through fabrication to AI deployment, with US participation. The significance is directional: India is formally aligning its chip supply chain with the US-anchored side of a semiconductor divide that is reshaping global trade. The membership criteria, chip-volume commitments, and export-control provisions are not yet public, which limits what enterprise procurement teams can act on immediately.

US export controls already restrict H100 and A100-class GPU access for certain markets. China, cut off from NVIDIA and AMD's top-tier products, is running an industrial policy track toward domestic chip alternatives — one that RAND describes as not yet at performance parity. Vietnam's G42 deal carries its own chip-sourcing dependencies tied to G42's supply relationships, which have drawn US regulatory scrutiny previously. India's Pax Silica membership positions it on the side of the supply chain that retains access to the best available training hardware. Whether that translates into faster delivery timelines or preferential export licensing for Indian buyers depends on terms that have not been published.

Data Centers and Energy: Long-Term Strategy, Near-Term Constraint

Adani announced a $100 billion plan to build renewable-powered, AI-ready data centers across India by 2035. The 2035 endpoint makes it irrelevant to any infrastructure decision being made in the next two or three years.

The power problem Adani is addressing is genuinely global. In the US, tech companies are bypassing strained utility grids through direct power purchase agreements with generators, which the Washington Post describes as a shadow power grid, to avoid interconnection queues that have delayed capacity by years in some markets. China's Eastern Data, Western Computing initiative takes a different route, rather than solving the power problem at the data center site, it moves compute to where power already exists, co-locating facilities with hydropower and wind surplus in Guizhou, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang.

India has no operational equivalent at scale. Enterprise teams evaluating colocation in India need to assess grid capacity and power purchase agreement terms at existing facilities now, not on the assumption that the Adani buildout resolves near-term constraints.

On connectivity, Google announced America-India Connect at the Summit — new fiber-optic routes between the US and India extending across the Southern Hemisphere, part of a referenced $15 billion India AI infrastructure investment. Route completion timelines, cable specifications, and confirmed capacity figures are not yet public. Today's India–US bandwidth runs through cables that in several cases are more than a decade old. The upgrade is real and coming. It is not a present-day operational change.

What Enterprise Leaders Should Actually Do With This

The Summit produced movement on every layer of the stack — compute, models, governance, supply chain, data centers, and connectivity. The honest read is that most of it marks the beginning of a process. Two things are operational today: the 38,000-GPU pool at ₹65 per hour, and the BharatGen model suite. Everything else — the additional GPUs, the Pax Silica terms, the governance institutions, the Adani data centers, the Google fiber routes — is a commitment with an unconfirmed delivery timeline.

For compute sourcing, enterprises with India-residency requirements work with the 38,000-GPU pool until the 20,000-GPU addition goes live with a confirmed vendor, location, and pricing structure. For model adoption, Param-2 should be benchmarked against current alternatives on domain-specific Indian-language tasks before any production commitment, independent coverage is thin, and the model is new. For compliance, build to the Digital Personal Data Protection Act and sectoral rules, not the proposed governance institutions that carry no enforcement authority yet. For chip procurement, hold existing supplier relationships until Pax Silica publishes approved vendors and export provisions.

The infrastructure war is real. India is in it. The gap with the US and China is also real, and one summit week, however dense its announcement log, does not close it.